Colonic Perforation as Initial Presentation of Amyloid Disease: Case Report and Literature Review

A. Ussia · S. Vaccari · A. Lauro · A. Caira · M. L. Tardio · O. Leone · I. R. Marino · V. D’Andrea · M. Cervellera · V. Tonini

Abstract

Introduction

Amyloidosis is an uncommon disease caused by the deposition of amyloid fibrils in tissues. This disease does not usually require surgical intervention, which could be warranted in the presence of complications such as bleeding, obstruction, or perforation. We present a case of primary amyloidosis of the colon in a patient affected by polymyositis who underwent Hartmann’s procedure after a spontaneous colonic perforation. After 2 months of well-being, the patient underwent two consecutive surgical procedures for stenosis of the ostomy orifice.

Areas Covered

A review of the literature has been performed, gathering case reports highlighting the distribution of this disease by age, gender, location, and treatment when available.

Expert Commentary

Gastrointestinal amyloid disease is a rare condition, and it could be considered among the rare causes of intestinal perforation. Timely surgical management is often necessary.

Case Report and Evolution

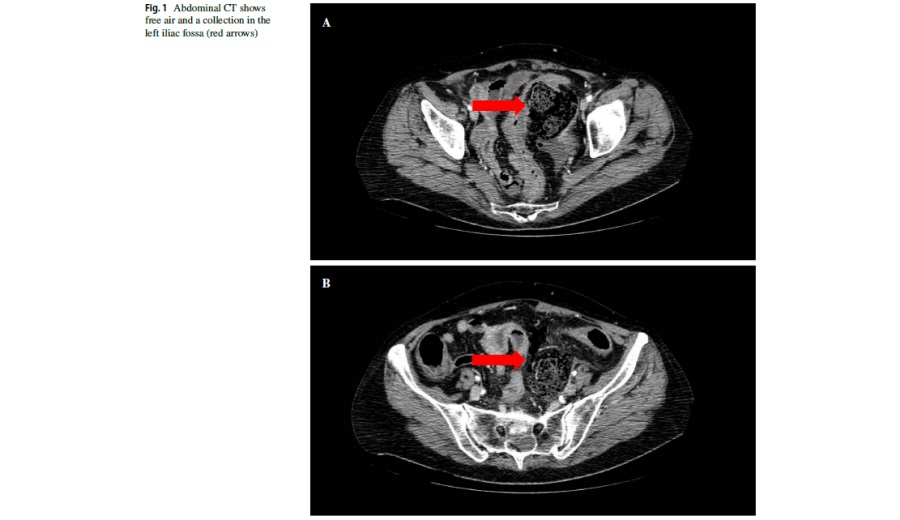

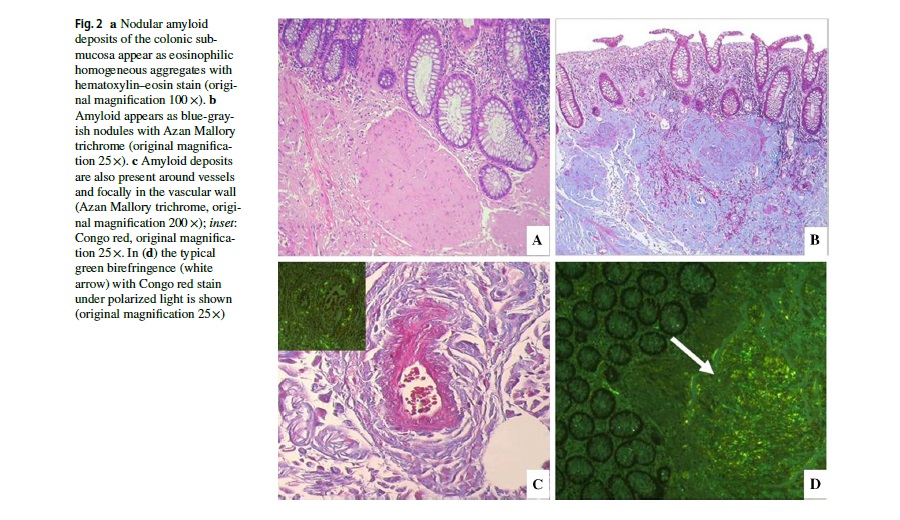

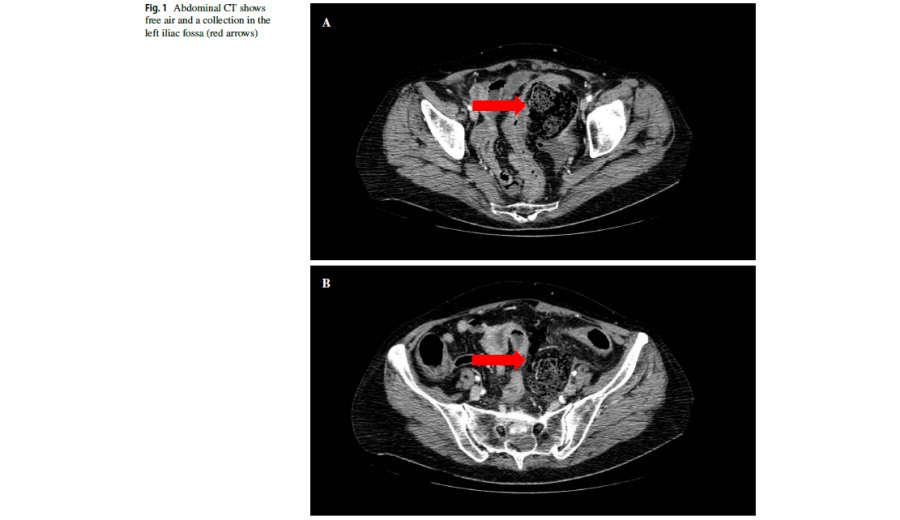

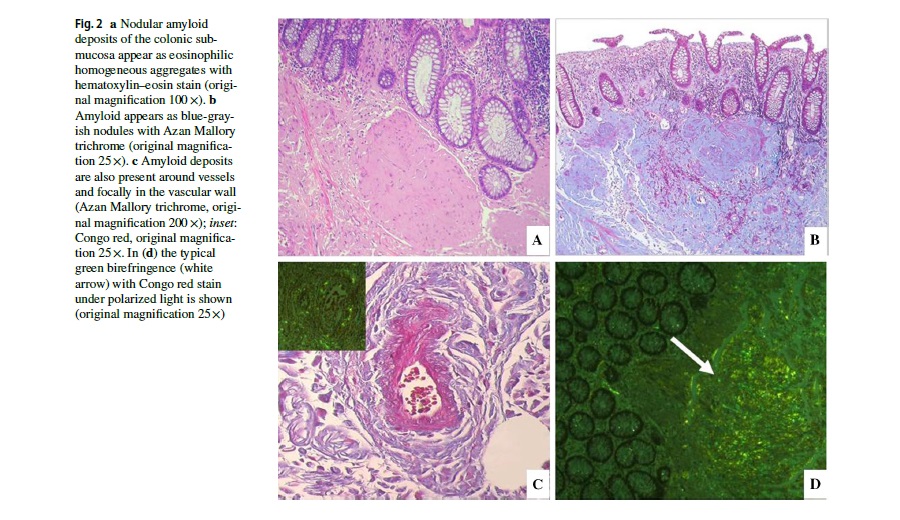

A 67-year-old woman was initially evaluated in the Emergency Department of St. Orsola University Hospital for generalized abdominal pain, fever, and signs of peritonitis. Her PMH included essential hypertension, HCV-related chronic liver disease, and polymyositis. Laboratory tests revealed eukocytosis and high serum levels of CRP. Abdominal CT scan revealed free air and a collection in the left iliac fossa (Fig. 1a, b). Emergency surgery was required and revealed a perforated colon that was resected with the Hartmann’s procedure with colostomy creation. Pathological analysis of the specimen revealed perforated ischemic colitis with diffuse amyloid deposits (Fig. 2). The patient was discharged in good clinical conditions on postoperative day 7.

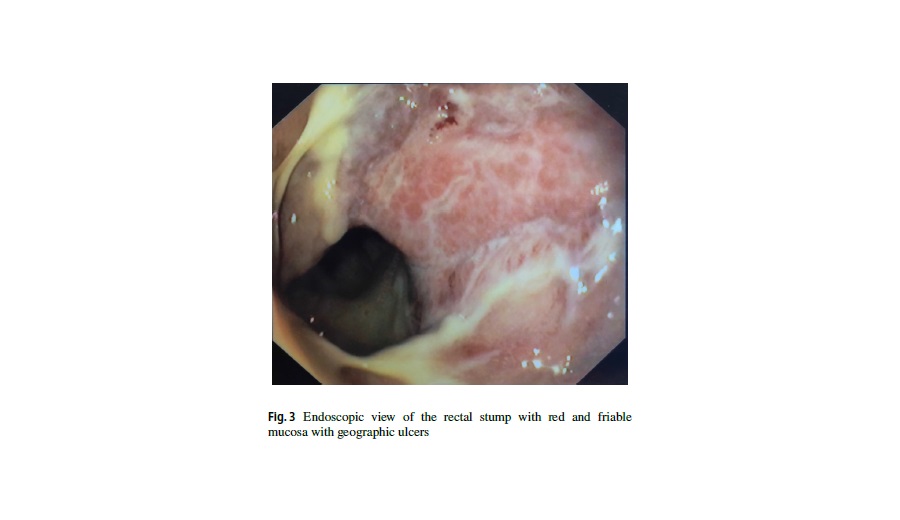

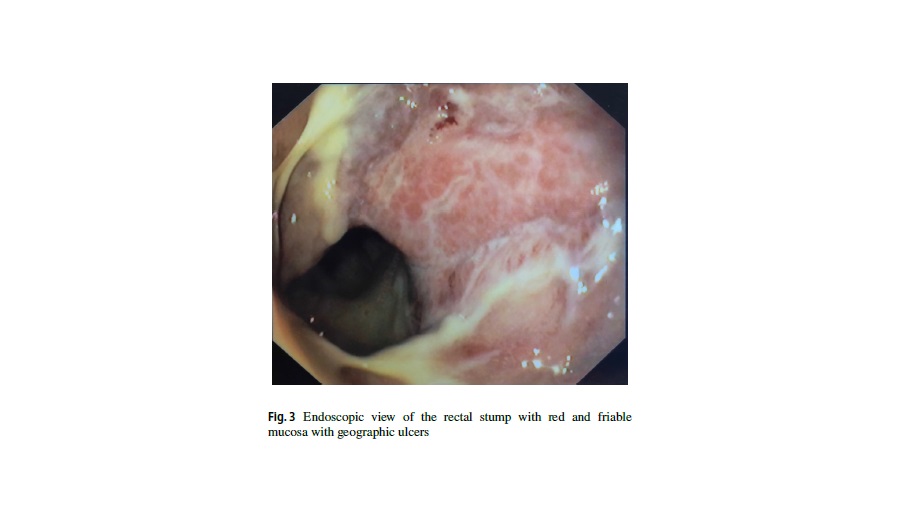

In the following 6 months, the patient was seen many times in the outpatient department for low-grade intestinal obstruction secondary to stenosis of the stoma orifice, treated conservatively with dilations of the ostomy, initially as an outpatient and later during two hospital admissions. Endoscopically, the rectal stump displayed red and friable mucosa with geographic ulcers (Fig. 3). Eventually, the patient underwent a limited revision of the stoma and removal of the previous colostomy, resection of the fibrotic tract, and creation of a new colostomy. Histological examination of the specimen showed severe and diffuse amyloidosis of the colon with multifocal ischemic colitis of indeterminate duration and stomal inflammation. Postoperatively, the patient was treated with a 3-month course of mesalamine with periodic digital exploration of the ostomy in order to prevent future stenosis.

After a period of good health, the patient inquired about the possibility of reversing the stoma. After a multidisciplinary case discussion, multiple full-thickness biopsies of the colon were obtained in order to better ascertain the extent of the disease. The biopsies showed that the disease was present in the entire residual colon. Therefore, in agreement with the patient, it was decided not to perform a stoma reversal in this case. Presently, the patient is in good condition with an adequately performing colostomy.

Discussion

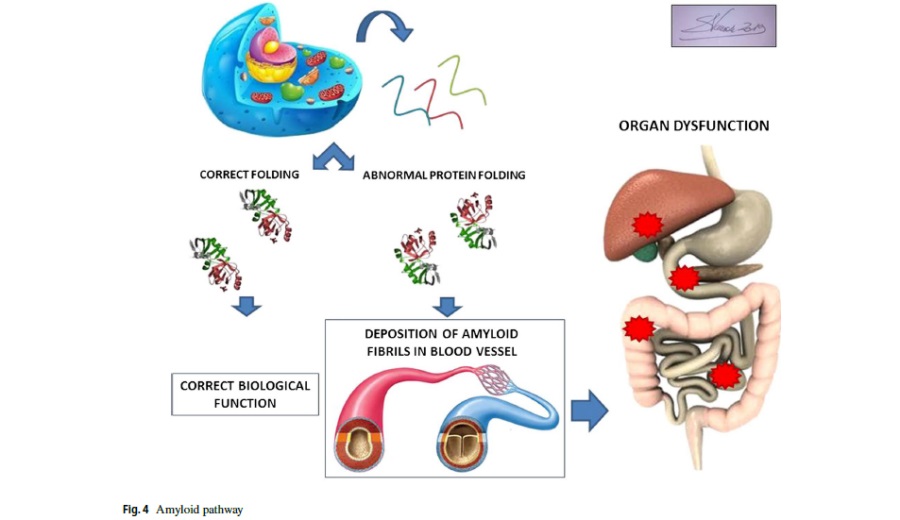

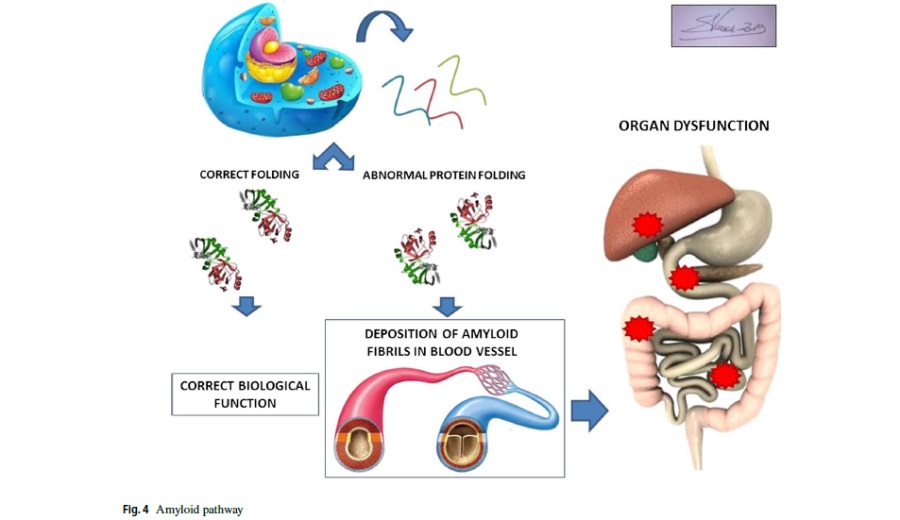

Amyloidosis is an uncommon disorder caused by abnormal protein folding. Systemic or localized deposition of these misfolding proteins as insoluble fibrils disrupts tissue structure and function (Fig. 4). Amyloidosis can be acquired or hereditary; the deposition of amyloid fibrils can occur in several situations such as in chronic inflammatory states, in association with the production of an abnormal protein with amyloidogenic propensity (e.g., certain immunoglobulin light chains from plasma cell dyscrasias), and after prolonged exposure to a normal concentrations of a structurally normal protein with weak inherent amyloidogenic potential (e.g., senile systemic amyloidosis).

The clinical features of amyloidosis are dependent on the organs involved. Systemic amyloidosis is the most common form. It is a very heterogeneous disease in its presentation and clinical course. Kidney involvement initially manifests as proteinuria or renal impairment, whereas cardiac amyloid deposition usually manifests as a restrictive cardiomyopathy and confers a poor prognosis. Among these patients, the median survival is 4–6 months after the appearance of congestive cardiac failure.

Amyloid deposition in the autonomic nervous system can cause orthostatic hypotension, impotence, urinary retention, and gastrointestinal dysfunction. Distal sensory deficit or a motor neuropathy due to peripheral neuropathy can occur. Cutaneous lesions, carpal tunnel syndrome, periorbital bruising, macroglossia, and lymphadenopathy can also be present.

Hepatomegaly is common due to the infiltration of amyloid fibrils or arises secondary to congestive cardiac failure. The typical biochemical profile of hepatic amyloidosis is characterized by an elevated liver function test. Although the gastrointestinal tract is susceptible to the deposition of amyloid materials, localized amyloidosis in this site is rare and gastrointestinal complications associated with this disease are exceptionally uncommon.

The diagnosis of amyloidosis is often made long after the onset of symptoms because of its nonspecific and varied clinical presentation, which can mimic many other conditions. Specific symptoms should trigger suspicion for a diagnosis of amyloidosis, such as nephrotic syndrome and heart failure; peripheral and autonomic neuropathy; a combination of carpal tunnel syndrome and heart failure in the elderly; and appropriate family history. Regular testing for the N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and urine sampling for albuminuria should be part of standard practice in patients with serum paraproteins such as a monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS) with abnormal free light chain ratio of lambda/ kappa free light chains, as an abnormality of either may herald development of amyloidosis. Diagnosis requires confirmation of the presence of amyloid fibrils by histology and is achieved by staining suspected amyloid tissue with Congo red; in the presence of amyloid fibrils, apple-green birefringence under cross-polarized light will be visualized by light microscopy.

Although amyloidosis is essentially a benign condition, systemic amyloidosis is almost invariably fatal and treatment is primarily supportive. Death usually follows a cardiac event or renal failure. Median survival is between 12 and 15 months with most patients succumbing within 3 years from diagnosis. When amyloidosis is associated with multiple myeloma, prognosis is even poorer with a median survival of only 4 months. The outcome is improved for secondary amyloidosis where a survival up to 5 years is common with occasional case reports documenting long-term survival.

Digestive localization of amyloidosis ranges from the oral cavity to the rectum, with the most common symptoms including abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, weight loss, and watery diarrhea. Nevertheless, involvement of the intestinal musculature may cause pseudo-obstruction. Organ infiltration by amyloid proteins occurs either in and around the walls of small submucosal blood vessels or within the mucosal or muscular layers of the gut wall. In most cases, the submucosal blood vessels are the earliest and most frequent site of amyloid deposition, with consequent blood vessel narrowing or occlusion, resulting in ischemia, infarction, or perforation, all of which have been reported in the literature although intestinal perforation is exceptionally rare.1The characteristics of the surgical procedures performed in the reported cases of amyloidotic gastrointestinal perforation are described in Table 1. The colon is the most frequent site of perforation since it has been described in 17 cases; most of them managed operatively (Table 2).

Our case was notable because the patient was asymptomatic until perforation, and there were no previous signs of amyloid disease. Preoperatively, the disease was not suspected and the diagnosis was first made on the histological specimen. We believe that polymyositis may have caused the deposition of amyloid in the colonic vessels leading to pneumoperitoneum, due to perforation by ischemia of the intestinal wall. The absolute lack of prodromal symptoms is unexplained, even if polymyositis often has nuanced symptomatology and a slow progression.

The patient denied the consent for further diagnostic investigations. After a few months of well-being, the onset of abdominal pain and obstruction in our patient leads us to carry out a revision of the stoma, taking down the previous colostomy and creating a new one. The possibility to reconnect the ostomy was then excluded.

Conclusions

The data reported in the literature showed that surgical treatment of amyloidosis affecting the gastrointestinal tract should be reserved for emergency procedures only. In patients treated by surgery due to massive bleeding, perforation, or obstruction, there may be an associated hemorrhagic diathesis or anastomotic dehiscence resulting in poor local healing. As in the case presented, any surgical procedure performed in a patient with amyloidosis disease is risky and may lead to complications, but it may be helpful in managing gastrointestinal amyloidosis and repeated if necessary.

Published online: 14 November 2019

© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019

06.60301809

06.60301809